Regularization

Why Don’t Control Depth

Why we don’t control the depth of networks to avoid overfitting?

In practice, it is always better to use the following methods to control overfitting instead of controlling the depth. In terms of optimization of objective, compared to shallow NNs, the deeper NNs contain significantly more local minima, but these minima turn out to be much better than that of shallow NNs in terms of their actual loss. Since Neural Networks are non-convex, it is hard to study these properties mathematically.

Additionally, the final loss of a shallower network can have a higher variance in practice, it may due to the number of minimas is small. Sometimes we get a good minima, and sometimes we get a very bad one, and it relies on the random initialization. However, for a deep network, all solutions are about equally as good, and rely less on the luck of random initialization.

In conclusion, you should use as big of a neural network as your computational budget allows, and use other regularization techniques to control overfitting.

L1 regularization

We usually need to regularize the weight parameters, but It is not common to regularize the bias parameters because they do not interact with the data through multiplicative interactions, and therefore do not have the interpretation of controlling the influence of a data dimension on the final objective.

L1 regularization regularizes the weight parameters by adding the term \(λ \| w \|_1\) to the objective for each weight \(w\).

The L1 regularization has the intriguing property that it leads the weight vectors to become sparse during optimization (i.e. very close to exactly zero). In other words, neurons with L1 regularization end up using only a sparse subset of their most important inputs and become nearly invariant to the “noisy” inputs.

L2 regularization

L2 regularization (also called weight decay) is a common form of regularization. It can be implemented by penalizing the squared magnitude of all parameters directly in the objective. That is, for every weight $w$ in the network, we add the term \(\frac{1}{2}λ\|w\|_2^2\) to the objective, where $λ$ is the regularization strength. (It is common to see the factor of $\frac{1}{2 }$ in front because then the gradient of this term with respect to the parameter $w$ is simply $λw$ instead of $2λw$.)

The L2 regularization has the intuitive interpretation of heavily penalizing peaky weight vectors and preferring diffuse weight vectors. Due to multiplicative interactions between weights and inputs this has the appealing property of encouraging the network to use all of its inputs a little rather than some of its inputs a lot. Lastly, notice that during gradient descent parameter update, using the L2 regularization ultimately means that every weight is decayed linearly: W += -lambda * W towards zero.

In comparison, final weight vectors from L2 regularization are usually diffuse, small numbers. In practice, if you are not concerned with explicit feature selection, L2 regularization can be expected to give superior performance over L1.

It is possible to combine the L1 regularization with the L2 regularization: \(λ_1 \| w \|_1 + λ_2 \| w \|_2^2\) (this is called Elastic net regularization).

Max Norm Constraints

Another form of regularization is to enforce an absolute upper bound on the magnitude of the weight vector for every neuron and use projected gradient descent to enforce the constraint. In practice, this corresponds to performing the parameter update as normal, and then enforcing the constraint by clamping the weight vector $w$ of every neuron to satisfy \(\|w\|_2<c\). Typical values of $c$ are on orders of 3 or 4. Some people report improvements when using this form of regularization. One of its appealing properties is that network cannot “explode” even when the learning rates are set too high because the updates are always bounded.

Dropout

Dropout is an extremely effective, simple and recently introduced regularization technique by Srivastava et al. that complements the other methods (L1, L2, maxnorm).

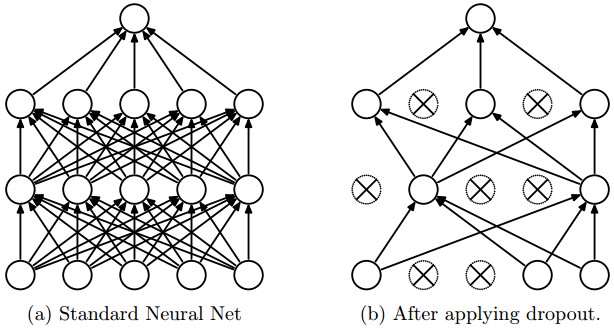

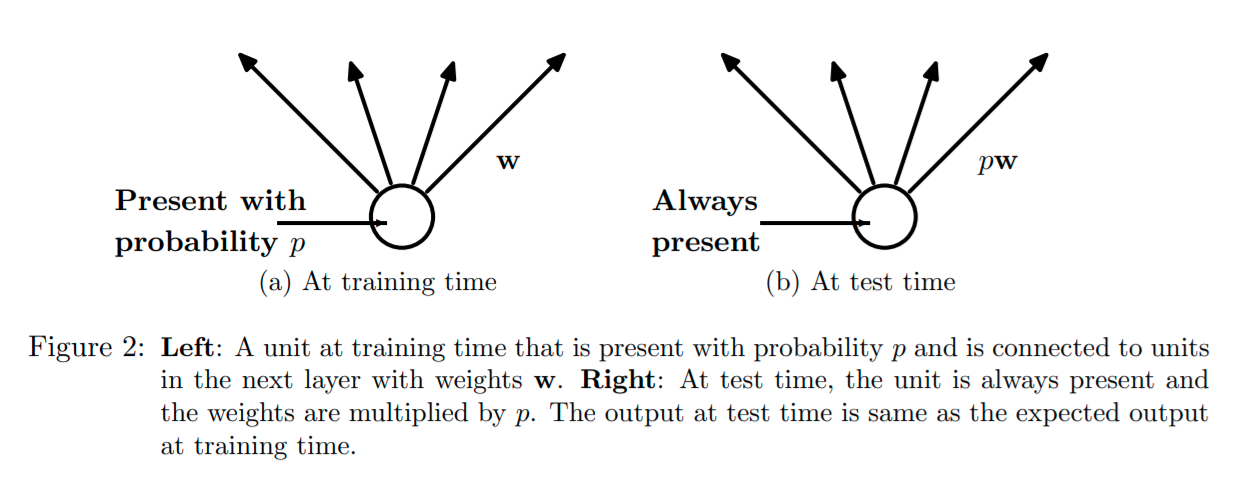

While training, at each iteration, dropout is implemented by only keeping a neuron active with some probability \(p\) (a hyperparameter), or setting it to zero temporarily otherwise, as shown below:

At test time, the weights of this network are scaled-down versions (multiplied by \(p\)) of the trained weights, as shown below:

A wider network may be required when using dropout.

Although dropout alone gives significant improvements, using dropout along with max norm constraints, large decaying learning rates and high momentum provides a significant boost over just using dropout, especially the max norm constraints.

Dropout prevents overfitting and provides a way of approximately combining exponentially many different neural network architectures efficiently. The following are three different motivations of dropout.

Motivations of Dropout

Dropout prevents neurons from co-adapting too much. During the training of a network, neurons may change in a way that they fix up the mistakes of the other neurons. This may lead to complex co-adaptations. This in turn leads to overfitting because these co-adaptations do not generalize to unseen data. With dropout, each hidden neuron in a neural network trained must learn to work with a randomly chosen sample of other neurons. This should reduce the coupling of neurons, and make each hidden neuron more robust and drive it towards creating useful features on its own without relying on other hidden neurons to correct its mistakes.

Dropout makes network learn multiple “thinned” networks. Applying dropout to a neural network amounts to sampling a “thinned” network from it. The thinned network consists of all the neurons that survived dropout. A neural net with \(n\) neurons, can be seen as a collection of \(2^n\) possible thinned neural networks, so training a neural network with dropout can be seen as training a collection of \(2^n\) thinned networks. At test time, we average these thinned networks by multiplying the weights by \(p\).

Dropout can be interpreted as a way of regularizing a network by adding noise to its hidden neurons.

Hyperparameters Tuning

The most common hyperparameters in Neural Networks include:

-

the number of neurons (width)

-

the number of layers (depth)

-

the initial learning rate

-

learning rate decay schedule (such as the decay constant)

-

regularization strength (L2 penalty, dropout strength)

Number of Neurons

Here are 3 rule-of-thumb methods for determining an acceptable number of neurons to use in the hidden layers [Reference]. The number of hidden neurons should be:

- between the size of the input layer and the size of the output layer.

- 2/3 the size of the input layer, plus the size of the output layer.

- less than twice the size of the input layer.

Use a Single Validation Set

In practice, we prefer one validation fold to cross-validation. In most cases a single validation set of respectable size substantially simplifies the code base, without the need for cross-validation with multiple folds.

Hyperparameter Ranges

Search for learning rate and regularization strength on log scale. For example, a typical sampling of the learning rate would look as follows: learning_rate = 10 ** uniform(-6, 1). That is, we are generating a random number from a uniform distribution, but then raising it to the power of \(10\).

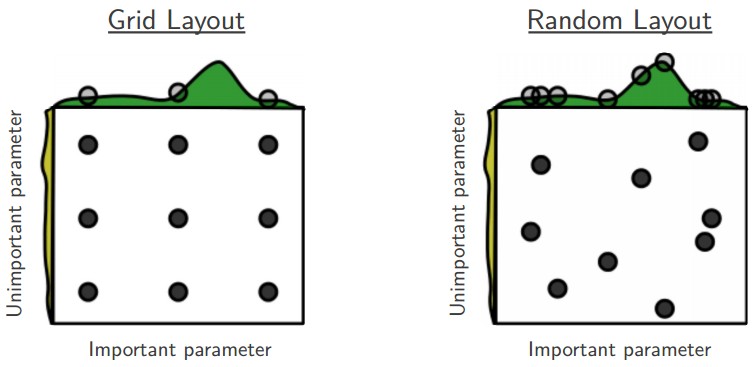

Prefer Random Search

We prefer random search to grid search. As argued by Bergstra and Bengio in Random Search for Hyper-Parameter Optimization, “randomly chosen trials are more efficient for hyper-parameter optimization than trials on a grid”. As it turns out, this is also usually easier to implement.

References:

Srivastava, Nitish , et al. “Dropout: A Simple Way to Prevent Neural Networks from Overfitting.” Journal of Machine Learning Research 15.1(2014):1929-1958.

CS231n Convolutional Neural Networks for Visual Recognition.