- Chapter 3. Strings, Vectors, and Arrays

- 3.2 Library

stringType - 3.3 Library

vectorType - 3.4 Introducing Iterators

- 3.5 Arrays

- 3.6 Multidimensional Arrays

Chapter 3. Strings, Vectors, and Arrays

The built-in types that we covered in Chapter 2 are defined directly by the C++ language. These types represent facilities present in most computer hardware, such as numbers or characters.

The standard library defines a number of additional types (string, vector, etc.) of a higher-level nature that computer hardware usually does not implement directly. Associated with string and vector are companion types known as iterators, which are used to access the characters in a string or the elements in a vector.

The built-in array type represents facilities of the hardware. As a result, arrays are less convenient to use than the library string and vector types.

3.1 Namespace using Declarations

A using declaration has the form

using namespace::name;

Once the using declaration has been made, we can access name directly.

A Separate using Declaration Is Required for Each Name

Headers Should Not Include using Declarations

Code inside headers (§ 2.6.3, p. 76) ordinarily should not use using declarations. The reason is that the contents of a header are copied into the including program’s text. If a header has a using declaration, then every program that includes that header gets that same using declaration. As a result, a program that didn’t intend to use the specified library name might encounter unexpected name conflicts.

A Note to the Reader

3.2 Library string Type

A string is a variable-length sequence of characters. To use the string type, we must include the string header. <string> is a header file in C++ std library, and string is defined in the std namespace.

#include <string>

using std::string;

3.2.1 Defining and Initializing strings

Ways to initialize a string.

string s1 // default initialization, s1 is the empty string with no characters

string s2 = s1 // s2 is a copy of s1; copy initialization

string s2(s1) // direct initialization

string s3 = "value" // s3 is a copy of the string literal, not including the null; copy initialization

string s3("value") // direct initialization

string s4(5, 'c') // initialize s4 with 5 copies of the character 'c', s4 is "ccccc"; direct initialization

Direct and Copy Forms of Initialization

When we initialize a variable using =, we are asking the compiler to copy initialize the object by copying the initializer on the right-hand side into the object being created. Otherwise, when we omit the =, we use direct initialization.

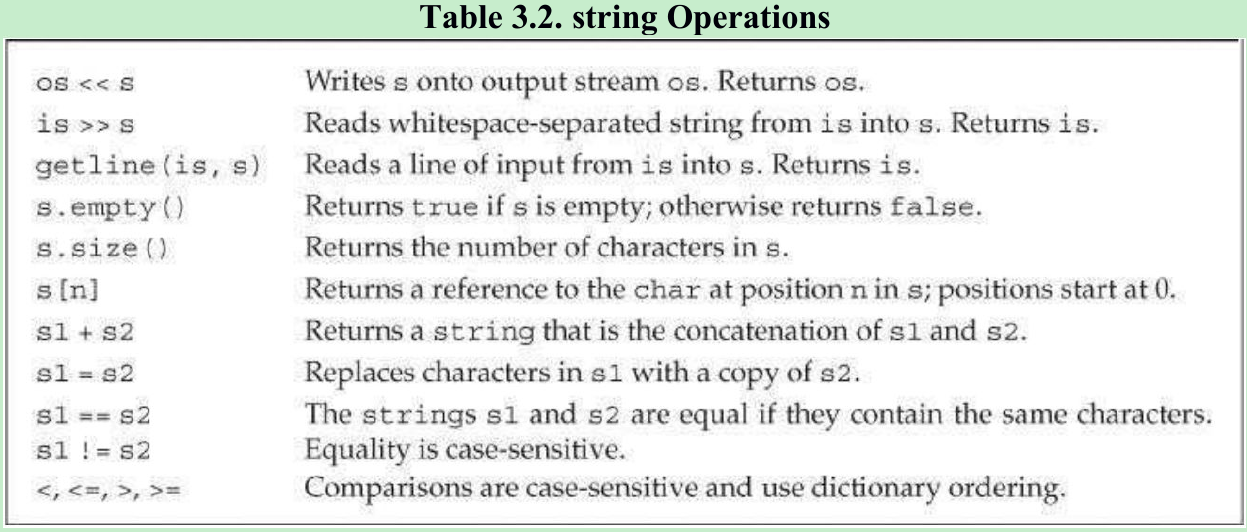

3.2.2 Operations on strings

Reading and Writing strings

Using getline to Read an Entire Line

The string empty and size Operations

The string::size_type Type

The type of the value returned by size function is string::size_type but not int or unsigned (§ 2.1.1, p. 34). string::size_type is an unsigned type (§ 2.1.1, p. 32) big enough to hold the size of any string.

string::size_type len = line.size();

auto len = line.size(); // equivalent to previous, len has type string::size_type

Because size returns an unsigned type, it is essential to remember that expressions that mix signed and unsigned data can have surprising results (§ 2.1.2, p. 36). For example, if n is an int that holds a negative value, then s.size() < n will almost surely evaluate as true, because the negative value in n will convert to a large unsigned value.

Comparing strings

Assignment for strings

Adding Two strings

Adding Literals and strings

3.2.3 Dealing with the Characters in a string

Processing Every Character? Use Range-Based for

The range for statement iterates through the elements in a given sequence and performs some operation on each value in that sequence. The syntactic form is

for (declaration : expression)

statement

where expression is an object of a type that represents a sequence. On each iteration, the variable in declaration is initialized from the value of the next element in expression.

string str("some string");

// print the characters in str one character to a line

for (auto c : str) // for every char in str

cout << c << endl; // print the current character followed by a newline

In this case c is of type char. On each iteration, the next character in str will be copied into c.

We can declare references to the characters in str to avoid copying them: for (auto &c : str). We can also declare constant references to the characters If we don’t need to edit them: for (auto &c : str).

Using a Range for to Change the Characters in a string

If we want to change the value of the characters in a string, we must define the loop variable as a reference type.

Converting a string to all uppercase letters:

string s("Hello World!!!");

// convert s to uppercase

for (auto &c : s) // for every char in s (note: c is a reference)

c = toupper(c); // c is a reference, so the assignment changes the char in s

cout << s << endl;

Processing Only Some Characters?

The subscript operator (the [] operator) takes a string::size_type (§ 3.2.2, p. 88) value that denotes the position of the character we want to access. The subscript operator [] returns a reference to the character at the given position.

The reference to the last character is s[s.size()-1].

Note: The result of using an index outside this range is undefined. By implication, subscripting an empty string is undefined.

The value in the subscript is referred to as “a subscript” or “an index”. If our index has a signed type, its value will be converted to the unsigned type that string::size_type represents (§ 2.1.2, p. 36).

Using a Subscript for Iteration

As a another example, we’ll change the first word in s to all uppercase:

// process characters in s until we run out of characters or we hit a whitespace

for (decltype(s.size()) index = 0; index != s.size() && !isspace(s[index]); ++index)

s[index] = toupper(s[index]); // capitalize the current character

CAUTION: SUBSCRIPTS ARE UNCHECKED

When we use a subscript, we must ensure that the subscript is in range. That is, the subscript must be >= 0 and < the size() of the string.

WARNING: The library is not required to check the value of an subscript. The result of using an out-of-range subscript is undefined.

Using a Subscript for Random Access

3.3 Library vector Type

A vector is a collection of objects, all of which have the same type. Every object in the collection has an associated index, which gives access to that object. A vector is often referred to as a container because it “contains” other objects.

We must include the <vector> header to use a vector. In our examples, we also assume that an appropriate using declaration is made:

#include <vector>

using std::vector;

A vector is a class template. C++ has both class and function templates.

Templates are not themselves functions or classes. Instead, they can be thought of as instructions to the compiler for generating classes or functions. The process that the compiler uses to create classes or functions from templates is called instantiation. When we use a template, we specify what kind of class or function we want the compiler to instantiate.

For a class template, we specify which class to instantiate by supplying additional information: We supply it inside a pair of angle brackets following the template’s name.

In the case of vector, the additional information we supply is the type of the objects the vector will hold:

vector<int> ivec; // ivec holds objects of type int

vector<Sales_item> Sales_vec; // holds Sales_items

vector<vector<string>> file; // vector whose elements are vectors

Note: vector is a template, not a type. Types generated from vector must include the element type, for example, vector<int>.

Because references are not objects, we cannot have a vector of references.

3.3.1 Defining and Initializing vectors

As with any class type, the vector template controls how we define and initialize vectors.

vector<string> svec; // default initialization; svec has no elements

The most common way of using vectors is to define an initially empty vector to which elements are added as their values become known at run time.

We can also supply initial value(s) for the element(s) when we define a vector.

vector<int> ivec; // initially empty

// give ivec some values

vector<int> ivec2(ivec); // copy elements of ivec into ivec2

vector<int> ivec3 = ivec; // copy elements of ivec into ivec3

vector<string> svec(ivec2); // error: svec holds strings, not ints

List Initializing a vector

Under the new standard, we can list initialize (§ 2.2.1, p. 43) a vector from a list of zero or more initial element values enclosed in curly braces:

vector<string> articles = {"a", "an", "the"};

Or

vector<string> articles{"a", "an", "the"};

Creating a Specified Number of Elements

vector<int> ivec(10, -1); // ten int elements, each initialized to -1

vector<string> svec(10, "hi!"); // ten strings; each element is "hi!"

Value Initialization

We can usually omit the value and supply only a size.

vector<int> ivec(10); // ten elements, each initialized to 0

vector<string> svec(10); // ten elements, each an empty string

List Initializer or Element Count?

vector<int> v1(10); // v1 has ten elements with value 0

vector<int> v2{10}; // v2 has one element with value 10

vector<int> v3(10, 1); // v3 has ten elements with value 1

vector<int> v4{10, 1}; // v4 has two elements with values 10 and 1

When we use parentheses, we are saying that the values we supply are to be used to construct the object.

When we use curly braces, {...}, we’re saying that, if possible, we want to list initialize the object. That is, if there is a way to use the values inside the curly braces as a list of element initializers, the class will do so. Only if it is not possible to list initialize the object will the other ways to initialize the object be considered.

On the other hand, if we use braces and there is no way to use the initializers to list initialize the object, then those values will be used to construct the object.

vector<string> v5{"hi"}; // list initialization: v5 has one element

vector<string> v6("hi"); // error: can't construct a vector from a string literal

vector<string> v7{10}; // v7 has ten default initialized elements

vector<string> v8{10, "hi"}; // v8 has ten elements with value "hi"

3.3.2 Adding Elements to a vector

vector<int> v2; // empty vector

for (int i = 0; i != 100; ++i)

v2.push_back(i); // append sequential integers to v2

// at end of loop v2 has 100 elements, values 0 ... 99

Read the input, storing the values we read in the vector:

// read words from the standard input and store them as elements in a vector

string word;

vector<string> text; // empty vector

while (cin >> word) {

text.push_back(word); // append word to text

}

Programming Implications of Adding Elements to a vector

The fact that we can easily and efficiently add elements to a vector greatly simplifies many programming tasks.

We cannot use a range for if the body of the loop adds elements to the vector.

3.3.3 Other vector Operations

vector<int> v{1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9};

for (auto &i : v) // for each element in v (note: i is a reference)

i* = i; // square the element value

for (auto i : v) // for each element in v

cout << i << " "; // print the element

cout << endl;

Note: To use size_type, we must name the type in which it is defined. A vector type always includes its element type (§ 3.3, p. 97):

vector<int>::size_type // ok

vector::size_type // error

We can compare two vectors only if we can compare the elements in those vectors.

Computing a vector Index

// count the number of grades by clusters of ten: 0--9, 10--19, ... 90--99, 100

vector<unsigned> scores(11, 0); // 11 buckets, all initially 0

unsigned grade;

while (cin >> grade) { // read the grades

if (grade <= 100) // handle only valid grades

++scores[grade/10]; // increment the counter for the current cluster

}

Subscripting Does Not Add Elements

3.4 Introducing Iterators

Like pointers (§ 2.3.2, p. 52), iterators give us indirect access to an object.

As with pointers, an iterator may be valid or invalid. A valid iterator either denotes an element or denotes a position one past the last element in a container. All other iterator values are invalid.

3.4.1 Using Iterators

Unlike pointers, we do not use the address-of operator to obtain an iterator. Instead, types that have iterators have members named begin and end that return iterators.

// the compiler determines the type of b and e; see § 2.5.2 (p. 68)

// b denotes the first element and e denotes one past the last element in v

auto b = v.begin(), e = v.end(); // b and e have the same type

The begin member returns an iterator that denotes the first element (or first character), if there is one.

The iterator returned by end member is often referred to as the off-the-end iterator or abbreviated as “the end iterator”. This iterator denotes a nonexistent element “off the end” of the container. It is used as a marker indicating when we have processed all the elements.

If the container is empty, the iterators returned by begin and end are equal—they are both off-the-end iterators.

In general, we do not know (or care about) the precise type that an iterator has. In this example, we used auto to define b and e (§ 2.5.2, p. 68).

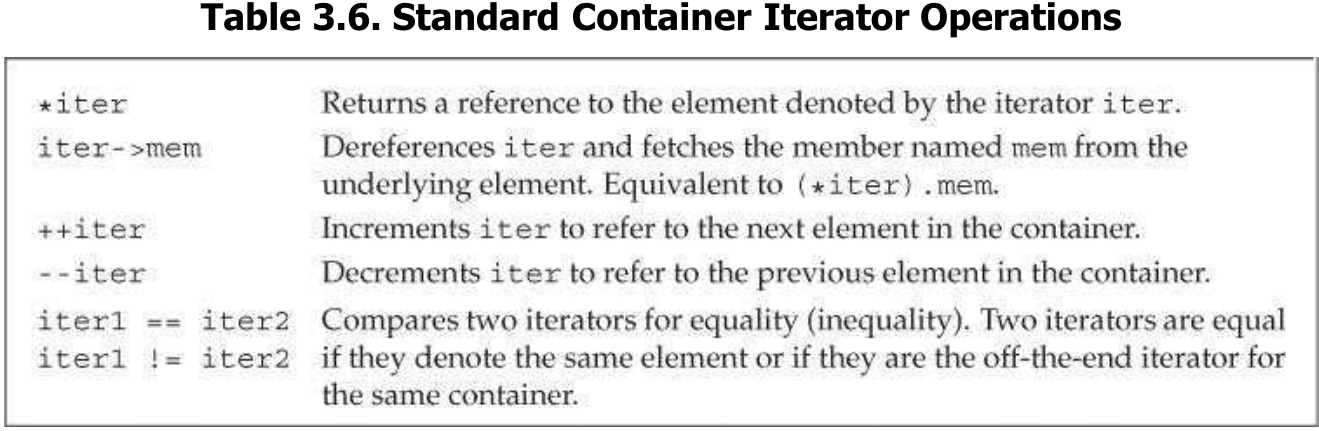

Iterator Operations

As with pointers, we can dereference an iterator to obtain the element denoted by an iterator. Also, like pointers, we may dereference only a valid iterator that denotes an element (§ 2.3.2, p. 53). Dereferencing an invalid iterator or an off-the-end iterator has undefined behavior.

As an example, we’ll rewrite the program from § 3.2.3 (p. 94) that capitalized the first character of a string using an iterator instead of a subscript:

string s("some string");

if (s.begin() != s.end()) { // make sure s is not empty

auto it = s.begin(); // it denotes the first character in s

*it = toupper(*it); // make that character uppercase

}

Moving Iterators from One Element to Another

Iterators use the increment (++) operator (§ 1.4.1, p. 12) to move from one element to the next.

Note: Because the iterator returned from end does not denote an element, it may not be incremented or dereferenced.

Change the case of the first word in a string by using iterator an it and the increment operator ++:

// process characters in s until we run out of characters or we hit a whitespace

for (auto it = s.begin(); it != s.end() && !isspace(*it); ++it)

*it = toupper(*it); // capitalize the current character

KEY CONCEPT: GENERIC PROGRAMMING

Only a few library types, vector and string being among them, have the subscript operator. Similarly, all of the library containers have iterators. Most of those iterators define the == and != operators but do not have the < operator.

Iterator Types

The library types that have iterators define types named iterator and const_iterator that represent actual iterator types:

vector<int>::iterator it; // it can read and write vector<int> elements

string::iterator it2; // it2 can read and write characters in a string

vector<int>::const_iterator it3; // it3 can read but not write elements

string::const_iterator it4; // it4 can read but not write characters

If a vector or string is const, we may use only its const_iterator type.

The begin and end Operations

The type returned by begin and end depends on whether the object on which they operator is const.

vector<int> v;

const vector<int> cv;

auto it1 = v.begin(); // it1 has type vector<int>::iterator

auto it2 = cv.begin(); // it2 has type vector<int>::const_iterator

For reasons we’ll explain in § 6.2.3 (p. 213), it is usually best to use a const type (such as const_iterator) when we need to read but do not need to write to an object. To let us ask specifically for the const_iterator type, the new standard introduced two new functions named cbegin and cend:

auto it3 = v.cbegin(); // it3 has type vector<int>::const_iterator

Combining Dereference and Member Access

Assuming it is an iterator into a vector of strings, we can check whether the string that it denotes is empty as follows:

(*it).empty()

To simplify expressions such as this one, the language defines the arrow operator (the -> operator). The arrow operator combines dereference and member access into a single operation. That is, it->mem is a synonym for (*it).mem.

// print each line in text up to the first blank line

for (auto it = text.cbegin(); it != text.cend() && !it->empty(); ++it)

cout << *it << endl;

Some vector Operations Invalidate Iterators

We cannot add elements to a vector inside a range for loop. We’ll explore how iterators become invalid in more detail in § 9.3.6 (p. 353).

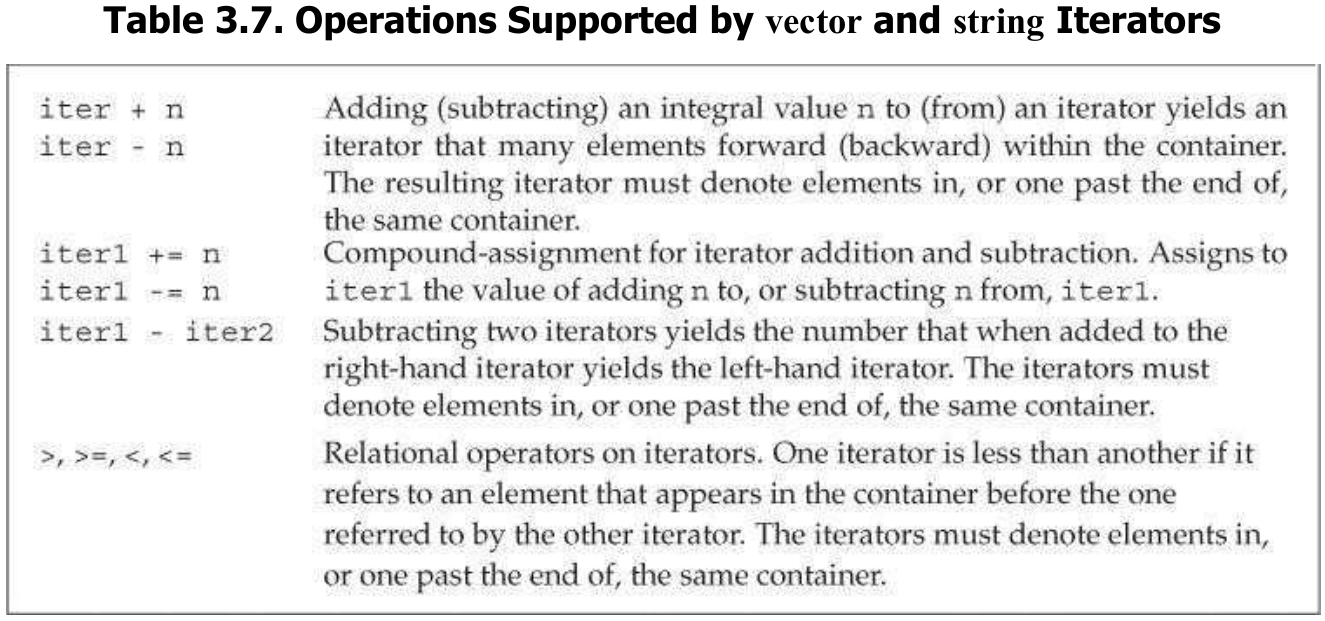

3.4.2 Iterator Arithmetic

Arithmetic Operations on Iterators

// compute an iterator to the element closest to the midpoint of vi

auto mid = vi.begin() + vi.size() / 2;

if (it < mid)

// process elements in the first half of vi

We can also subtract two iterators to get the distance that refers to the amount by which we’d have to change one iterator to get the other. The result type is a signed integral type named difference_type.

Using Iterator Arithmetic

Do a binary search using iterators as follows:

// text must be sorted

// beg and end will denote the range we're searching

auto beg = text.begin(), end = text.end();

auto mid = text.begin() + (end - beg)/2; // original midpoint

// while there are still elements to look at and we haven't yet found sought

while (mid != end && *mid != sought) {

if (sought < *mid) // is the element we want in the first half?

end = mid; // if so, adjust the range to ignore the second half

else // the element we want is in the second half

beg = mid + 1; // start looking with the element just after mid

mid = beg + (end - beg)/2; // new midpoint

}

3.5 Arrays

An array is a data structure that is similar to the library vector type (§ 3.3, p. 96) but offers a different trade-off between performance and flexibility. Like a vector, an array is a container of unnamed objects of a single type that we access by position. Unlike a vector, arrays have fixed size; we cannot add elements to an array. Because arrays have fixed size, they sometimes offer better run-time performance for specialized applications.

3.5.1 Defining and Initializing Built-in Arrays

Arrays are a compound type (§ 2.3, p. 50). An array declarator has the form a[d], where a is the name being defined and d is the dimension of (the number of elements in) the array. The dimension is part of the array’s type and must be known at compile time, which means that the dimension must be a constant expression (§ 2.4.4, p. 65):

unsigned cnt = 42; // not a constant expression

constexpr unsigned sz = 42; // constant expression (§ 2.4.4, p. 66)

int arr[10]; // array of ten ints

int *parr[sz]; // array of 42 pointers to int

string bad[cnt]; // error: cnt is not a constant expression

string strs[get_size()]; // ok if get_size is constexpr, error otherwise

By default, the elements in an array are default initialized (§ 2.2.1, p. 43).

WARNING: As with variables of built-in type, a default-initialized array of built-in type that is defined inside a function will have undefined values.

As with vector, arrays hold objects. Thus, there are no arrays of references.

Explicitly Initializing Array Elements

We can list initialize (§ 3.3.1, p. 98) the elements in an array. When we do so, we can omit the dimension and let the compiler infers it from the number of initializers.

const unsigned sz = 3;

int ia1[sz] = {0, 1, 2}; // array of three ints with values 0, 1, 2

int a2[] = {0, 1, 2}; // an array of dimension 3

int a3[5] = {0, 1, 2}; // equivalent to a3[] = {0, 1, 2, 0, 0}

string a4[3] = {"hi", "bye"}; // same as a4[] = {"hi", "bye", ""}

int a5[2] = {0, 1, 2}; // error: too many initializers

Character Arrays Are Special

Character arrays have an additional form of initialization: We can initialize such arrays from a string literal (§ 2.1.3, p. 39). When we use this form of initialization, it is important to remember that string literals end with a null character. That null character is copied into the array along with the characters in the literal:

char a1[] = {'C', '+', '+'}; // list initialization, no null

char a2[] = {'C', '+', '+', '\0'}; // list initialization, explicit null

char a3[] = "C++"; // null terminator added automatically

const char a4[6] = "Daniel"; // error: no space for the null!

The dimension of a1 is 3; the dimensions of a2 and a3 are both 4.

No Copy or Assignment

int a[] = {0, 1, 2}; // array of three ints

int a2[] = a; // error: cannot initialize one array as a copy of another

a2 = a; // error: cannot assign one array to another

WARNING: Some compilers allow array assignment as a compiler extension. It is usually a good idea to avoid using nonstandard features. Programs that use such features, will not work with a different compiler.

Understanding Complicated Array Declarations

Defining a pointer or reference to an array is a bit complicated:

int *ptrs[10]; // ptrs is an array of ten pointers to int

int &refs[10] = /* ? */; // error: no arrays of references

int (*Parray)[10] = &arr; // Parray points to an array of ten ints

int (&arrRef)[10] = arr; // arrRef refers to an array of ten ints

By default, type modifiers bind right to left. Reading the definition of ptrs from right to left (§ 2.3.3, p. 58) is easy: We see that we’re defining an array of size 10, named ptrs, that holds pointers to int.

As for the definition of Parray, reading from the inside out makes it easier to understand the type of Parray: (*Parray) says that Parray is a pointer; [10] says Parray points to an array of size 10; int says the elements in that array are ints. Thus, Parray is a pointer to an array of 10 ints. Similarly, arrRef is a reference to an array of 10 ints.

Of course, there are no limits on how many type modifiers can be used:

int *(&arry)[10] = ptrs; // arry is a reference to an array of 10 pointers to int

Reading this declaration from the inside out: (&arry) says arry is a reference; [10] says arry points to an array of size 10; int * says the elements in the array are pointers to int.

Tip: It can be easier to understand array declarations by starting with the array’s name and reading them from the inside out.

3.5.2 Accessing the Elements of an Array

As with the library vector and string types, we can use a range for or the subscript operator to access elements of an array.

When we use a variable to subscript an array, we normally should define that variable to have type size_t. size_t is a machine-specific unsigned type that is guaranteed to be large enough to hold the size of any object in memory.

Reimplement our grading program from § 3.3.3 (p. 104) to use an array:

// count the number of grades by clusters of ten: 0--9, 10--19, ... 90--99, 100

unsigned scores[11] = {}; // 11 buckets, all value initialized to 0

unsigned grade;

while (cin >> grade) {

if (grade <= 100)

++scores[grade/10]; // increment the counter for the current cluster

}

As in the case of string or vector, it is best to use a range for when we want to traverse the entire array.

for (auto i : scores) // for each counter in scores

cout << i << " "; // print the value of that counter

cout << endl;

As with string and vector, it is up to the programmer to ensure that the subscript value is in range. Nothing stops a program from stepping across an array boundary except careful attention to detail and thorough testing of the code. It is possible for programs to compile and execute yet still be fatally wrong.

WARNING: The most common source of security problems are buffer overflow bugs. Such bugs occur when a program fails to check a subscript and mistakenly uses memory outside the range of an array or similar data structure.

3.5.3 Pointers and Arrays

In C++ pointers and arrays are closely intertwined. In particular, when we use an array, the compiler ordinarily converts the array to a pointer.

The elements in an array are objects. As with any other object, we can obtain a pointer to an array element by taking the address of that element:

string nums[] = {"one", "two", "three"}; // array of strings

string *p = &nums[0]; // p points to the first element in nums

However, arrays have a special property—in most places when we use an array, the compiler automatically substitutes a pointer to the first element:

string *p2 = nums; // equivalent to `string *p2 = &nums[0]`

Note: In most expressions, when we use an object of array type, we are really using a pointer to the first element in that array.

Operations on arrays are often really operations on pointers.

Pointers Are Iterators

Pointers that address elements in an array have additional operations beyond those we described in § 2.3.2 (p. 52). In particular, pointers to array elements support the same operations as iterators on vectors or strings (§ 3.4, p. 106). For example, we can use the increment operator to move from one element in an array to the next:

int arr[] = {0,1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9};

int *p = arr; // p points to the first element in arr

++p; // p points to arr[1]

Just as we can use iterators to traverse the elements in a vector, we can use pointers to traverse the elements in an array.

We can obtain an off-the-end pointer by taking the address of the nonexistent element one past the last element of an array:

int *e = &arr[10]; // pointer just past the last element in arr

Like an off-the-end iterator (§ 3.4.1, p. 106), an off-the-end pointer does not point to an element. As a result, we may not dereference or increment an off-the-end pointer, and the only thing we can do with it is to take its address.

Using these pointers we can write a loop to print the elements in arr as follows:

for (int *b = arr; b != e; ++b)

cout << *b << endl; // print the elements in arr

The Library begin and end Functions

Although we can compute an off-the-end pointer, doing so is error-prone. To make it easier and safer to use pointers, the new library includes two functions, named begin and end. These functions are defined in the iterator header. They take an argument that is an array:

int *beg = begin(arr); // pointer to the first element in arr

int *last = end(arr); // pointer one past the last element in arr

Note: A pointer “one past” the end of a built-in array behaves the same way as the iterator returned by the end operation of a vector.

Pointer Arithmetic

Pointers that address array elements can use all the iterator operations listed in Table 3.6 (p. 107) and Table 3.7 (p. 111).

When we add (or subtract) an integral value to (or from) a pointer, the result is a new pointer. That new pointer points to the element the given number ahead of (or behind) the original pointer:

constexpr size_t sz = 5;

int arr[sz] = {1,2,3,4,5};

int *ip = arr; // equivalent to int *ip = &arr[0]

int *ip2 = ip + 4; // ip2 points to arr[4], the last element in arr

// ok: arr is converted to a pointer to its first element; p points one past the end of arr

int *p = arr + sz; // use caution -- do not dereference!

int *p2 = arr + 10; // error: arr has only 5 elements; p2 has undefined value

Computing a pointer more than one past the last element is an error, although the compiler is unlikely to detect such errors.

As with iterators, subtracting two pointers gives us the distance between those pointers. The pointers must point to elements in the same array:

auto n = end(arr) - begin(arr); // n is 5, the number of elements in arr

The result of subtracting two pointers is a library type named ptrdiff_t. Like size_t, the ptrdiff_t type is a machine-specific type and is defined in the cstddef header.

Traverse the elements in arr as follows:

int *b = arr, *e = arr + sz;

while (b < e) {

// use *b

++b;

}

It is worth noting that pointer arithmetic is also valid for null pointers (§ 2.3.2, p. 53) and for pointers that point to an object that is not an array.

Interaction between Dereference and Pointer Arithmetic

The result of adding an integral value to a pointer is itself a pointer.

int ia[] = {0,2,4,6,8}; // array with 5 elements of type int

int last = *(ia + 4); // ok: initializes last to 8, the value of ia[4]

int last = *ia + 4; // ok: equivalent to ia[0] + 4

Subscripts and Pointers

In most places when we use the name of an array, we are really using a pointer to the first element in that array.

When we subscript an array, we are really subscripting a pointer to an element in that array:

int i = ia[2]; // ia is converted to a pointer to the first element in ia; ia[2] fetches the element to which (ia + 2) points

is equivalent to

int *p = ia; // p points to the first element in ia

int i = *(p + 2); // equivalent to int i = ia[2]

We can use the subscript operator on any pointer, as long as that pointer points to an element (or one past the last element) in an array:

int *p = &ia[2]; // p points to the element indexed by 2

int j = p[1]; // p[1] is equivalent to *(p + 1),

// p[1] is the same element as ia[3]

int k = p[-2]; // p[-2] is the same element as ia[0]

This last example points out an important difference between arrays and library types such as vector and string that have subscript operators. The library types force the index used with a subscript to be an unsigned value. The built-in subscript operator does not. The index used with the built-in subscript operator can be a negative value. Of course, the resulting address must point to an element in (or one past the end of) the array to which the original pointer points.

3.5.4 C-Style Character Strings

WARNING: Although C++ supports C-style strings, they should not be used by C++ programs. C-style strings are a surprisingly rich source of bugs and are the root cause of many security problems. They’re also harder to use!

C Library String Functions

Comparing Strings

Caller Is Responsible for Size of a Destination String

Tip: For most applications, in addition to being safer, it is also more efficient to use library strings rather than C-style strings.

3.5.5 Interfacing to Older Code

Many C++ programs predate the standard library and do not use the string and vector types. Moreover, many C++ programs interface to programs written in C or other languages that cannot use the C++ library. Hence, programs written in modern C++ may have to interface to code that uses arrays and/or C-style character strings. The C++ library offers facilities to make the interface easier to manage.

Mixing Library strings and C-Style Strings

Using an Array to Initialize a vector

ADVICE: USE LIBRARY TYPES INSTEAD OF ARRAYS

Pointers and arrays are surprisingly error-prone. Modern C++ programs should use vectors and iterators instead of built-in arrays and pointers, and use strings rather than C-style array-based character strings.

3.6 Multidimensional Arrays

Strictly speaking, there are no multidimensional arrays in C++. What are commonly referred to as multidimensional arrays are actually arrays of arrays.

int ia[3][4]; // ia is an array of size 3; each element is an array of int s of size 4

// arr is an array of size 10; each element is a 20-element array whose elements are arrays of 30 int s

int arr[10][20][30] = {0}; // initialize all elements to 0

In a two-dimensional array, the first dimension is usually referred to as the row and the second as the column.

Initializing the Elements of a Multidimensional Array

int ia[3][4] = { // three elements; each element is an array of size 4

{0, 1, 2, 3}, // initializers for the row indexed by 0

{4, 5, 6, 7}, // row 1

{8, 9, 10, 11} // row 2

};

is equivalent to

int ia[3][4] = {0,1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11};

As is the case for single-dimension arrays, elements may be left out of the initializer list.

// initialize only the first element of each row; the remaining elements are initialized to 0

int ia[3][4] = { {0}, {4}, {8} };

// explicitly initialize row 0; the remaining elements are initialized to 0

int ix[3][4] = {0, 3, 6, 9};

Subscripting a Multidimensional Array

// assigns the first element of arr to the last element in the last row of ia

ia[2][3] = arr[0][0][0];

// defines row as a reference to an array of four ints; binds this reference to the second four-element array in ia

int (&row)[4] = ia[1];

Use nested for loops to process the elements in a multidimensional array:

constexpr size_t rowCnt = 3, colCnt = 4;

int ia[rowCnt][colCnt]; // 12 uninitialized elements

// for each row

for (size_t i = 0; i != rowCnt; ++i) {

// for each column within the row

for (size_t j = 0; j != colCnt; ++j) {

// assign the element's positional index as its value

ia[i][j] = i * colCnt + j;

}

}

Using a Range for with Multidimensional Arrays

Under the new standard we can simplify the previous loop by using a range for:

size_t cnt = 0;

for (auto &row : ia) // for every element in the outer array

for (auto &col : row) { // for every element in the inner array

col = cnt; // give this element the next value

++cnt; // increment cnt

}

The first for iterates through the elements in ia. Those elements are arrays of size 4. Thus, the type of row is a reference to an array of four ints. The second for iterates through one of those 4-element arrays. Hence, col is int&.

It is worth noting that we define row and col as references rather than for (auto row : ia) and for (auto col : row) to avoid copying them. This way is more efficient than copying when row and col is large.

The following loop does not write to the elements, yet we still define the control variable of the outer loop as a reference.

for (const auto &row : ia)

for (auto col : row)

cout << col << endl;

Note: To use a multidimensional array in a range for, the loop control variable for all but the innermost array must be references.

Pointers and Multidimensional Arrays

As with any array, when we use the name of a multidimensional array, it is automatically converted to a pointer to the first element in the array. For here the first element is the first inner array in the multidimensional array.

int ia[3][4]; // array of size 3; each element is an array of int s of size 4

int (*p)[4] = ia; // pointer to an array of four ints

p = &ia[2]; // p now points to the last element in ia

Applying the strategy from § 3.5.1 (p. 115), we start by noting that (*p) says p is a pointer. Looking right, we see that the object to which p points has a dimension of size 4, and looking left that the element type is int. Hence, p is a pointer to an array of four ints.

Note: The parentheses in this declaration are essential:

int *ip[4]; // array of pointers to int

With the advent of the new standard, we can often avoid having to write the

type of a pointer into an array by using auto or decltype (§ 2.5.2, p. 68):

// print the value of each element in ia, with each inner array on its own line

// initialize p to point to the first array in ia

// the increment, ++p, moves p to point to the next row (i.e., the next element, the next array) in ia

for (auto p = ia; p != ia + 3; ++p) {

// initialize q point to the first element of the array to which p points; this array is of four ints; thus q points to an int

for (auto q = *p; q != *p + 4; ++q)

cout << *q << ''; // prints the int value to which q points

cout << endl;

}

We can even more easily write this loop using the library begin and end functions (§ 3.5.3, p. 118):

for (auto p = begin(ia); p != end(ia); ++p) {

for (auto q = begin(*p); q != end(*p); ++q)

cout << *q << '';

cout << endl;

}

Type Aliases Simplify Pointers to Multidimensional Arrays

Define int_array as a name for the type “array of four ints”:

using int_array = int[4]; // new style type alias declaration; see § 2.5.1 (p. 68)

Or equivalently:

typedef int int_array[4]; // § 2.5.1 (p. 67)

Then we can rewrite the first line as:

for (int_array *p = ia; p != ia + 3; ++p) {

// ...

Chapter Summary

Among the most important library types are vector and string. A string is a variable-length sequence of characters, and a vector is a container of objects of a single type.

Iterators allow indirect access to objects stored in a container. Iterators are used to access and navigate between the elements in strings and vectors.

Arrays and pointers to array elements provide low-level analogs to the vector and string libraries. In general, the library classes should be used in preference to low-level array and pointer alternatives built into the language.

Defined Terms

buffer overflow Serious programming bug that results when we use an index that is out-of-range for a container, such as a string, vector, or an array.

class template A blueprint from which specific class types can be created. To use a class template, we must specify additional information. For example, to define a vector, we specify the element type: vector<int> holds ints.

container A type whose objects hold a collection of objects of a given type. vector is a container type.

iterator A type used to access and navigate among the elements of a container.

range for Control statement that iterates through a specified collection of values.

string Library type that represents a sequence of characters.

vector Library type that holds a collection of elements of a specified type.

References

[1] Lippman, Stanley B., Josée Lajoie, and Barbara E. Moo. C++ Primer. Addison-Wesley Professional, 2012.

[2] Prata, Stephen. C++ primer plus. Addison-Wesley Professional, 2011.